River hazards | Things to consider | File a float plan | A note on paddling solo

Moving water is an amazing thing. It carves the highest mountains down to sea level, ferries continental crust to the ocean floor, and gives birth to entire ecosystems. It creates runs, riffles, rapids, and cascades, from the babble of the creek in your backyard to the thunder of Niagara Falls. The incredible power of moving water also means that rivers contain hazards and pose challenges not found in stillwater lakes and ponds. This page describes those hazards, as well as a few others general to watersports or outdoor recreation, and discusses how to approach and mitigate them. With the proper knowledge, equipment, and mindset, your river trip can be as safe as any daily activity.

The first rule of river safety is to always wear a personal flotation device (PFD or life jacket). All states in the Northeast have laws requiring paddlecraft to carry PFDs, though laws requiring them to be worn are situational and inconsistent. Notably, a PFD does you no good if it is sitting in your boat when you go overboard. There are many statistics that highlight the importance of wearing these lifesaving devices, but one that the author finds particularly striking is that of the 74 people who drowned in the upper Delaware from 1980-2021, not one of them was wearing a life jacket. Get a PFD that is well-fitting and comfortable, and wear it.

River hazards

| Hazard | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Rapids | Fast, turbulent water arising in areas with steep gradient. Rapids are classified from I-VI and may contain many of the hazards listed below, including rocks, eddy lines, holes, and strainers. Know the difficulty of the rapids in the section you are paddling, and learn to read the river. Scout any rapid you are uncertain about and portage if you are not confident in your ability to run it safely. | |

| Rocks | A good place to stop for lunch, but unpleasant to crash into when running a rapid. Undercut rocks are particularly dangerous, as a paddler can become trapped against them underwater. If you are on a collision course with a rock and cannot avoid it, lean downstream toward the rock as you impact it. Leaning away from the rock is likely to upset your boat. | |

| Eddy lines | The unstable boundaries between currents moving in opposite directions, often found in rapids, near shore, and behind any obstacle to flow in moving water. Approach eddy lines at a 45-degree angle and lean downstream (relative to the direction of the current you are entering) when crossing. | |

| Holes | Also called hydraulics, these are the white, frothy foam piles formed when water pours forcefully over an obstruction and flows back upstream to fill the temporary void created by that action. While some holes are friendly surfing spots for playboaters, others are “sticky” and tough to manoeuvre out of once inside. Escaping a hole usually involves paddling to its edge, where the backwash is weaker. | |

| Strainers and sweepers | Downed trees or tree limbs partially submerged in the water (strainers) or hanging low above the water (sweepers) that present an entanglement risk, especially in swift current. Strainers and logjams can completely block narrower channels and require portaging. If you are unable to avoid a strainer, try to pull yourself on top of it as you approach. | |

| Low-head dams | Usually built for recreation and/or small-scale industrial diversion, these structures span the entire width of the channel and allow water to flow over their crest. The sudden drop in elevation creates a powerful recirculating current at the base (essentially a river-wide hole) that is virtually impossible to escape. Some shorter, broken dams can be run, though breaches tend to ensnare strainers and other debris. From upstream, a low-head dam usually appears as a subtle horizon line and may be hard to spot. Always know whether the river section you are paddling contains these dams, where they are located, and how they are best portaged. Approach with extreme caution, especially when the current is swift, and stay out of the exclusion zone (generally 100 ft upstream of the lip and 50 ft downstream of the boil unless otherwise posted). | |

| Controlled-release dams | Usually built for flood control, drinking water storage, and/or power generation, these are large earthfill and concrete structures with control gates that regulate the amount of water released downstream. While there is no risk of accidentally going over the top of a controlled-release dam (unless the spillway is engaged, possibly), water levels immediately below these dams can rise and fall very rapidly as the release is ratcheted up or down. | |

| Wing dams and jetties | Built to channelise the main flow, protect the downstream shoreline from erosion, or redirect water into a canal, these are arms of stone, concrete, or wood that extend into the channel but do not fully impede waterflow. Give a wide berth to these structures at high water, as the same hydraulics found below low-head dams exist when water pours over a wing dam or jetty. | |

| Eel weirs | V-shaped lines of rocks that funnel eels into a trap at the point when active. These are especially common on the upper Delaware and middle Susquehanna. Pass left or right of the V altogether and avoid going into the trap or over the walls. | |

| Bridge piers | Strong current creates turbulent and chaotic flow on the downstream side of bridge piers and can pin a boat against the upstream side. Bridge piers are also prime gathering spots for strainers, which may block passage under some or all spans of the bridge. | |

| Water intakes | Structures through which river water is drawn for consumption or storage. Know where these are and respect signage warning river users to stay clear. | |

| Weather | Strong winds can make boat control a challenge, small streams can rise very rapidly after heavy rain, and the river is not the place to be during a pop-up summer afternoon thunderstorm. Check the weather forecast (the author recommends NWS probabilistic hourly forecasts—example), river levels, and accumulated rainfall before going on the water. | |

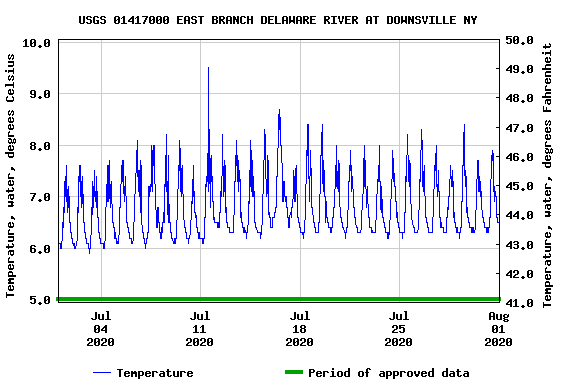

| Cold water | Even when the air temperature is warm, sudden immersion in cold water may lead to cardiovascular shock and accidental water inhalation. At water temperatures below 10 °C (50 °F), rapid loss of dexterity can make it difficult or impossible to self-rescue or swim to shore. Most rivers in NY and PA do not reach 15 °C (59 °F) until late May or later. Some river sections, such as those downstream of certain bottom-release dams, are perennially cold. Regardless of air temperature, wear a wetsuit when the water temperature is 7-15 °C (45-59 °F) and a drysuit below 7 °C (45 °F). In all weather, avoid slow-drying cotton and pack a change of clothes in a watertight bag. | |

| Deep/wide water | Although deep, wide sections of rivers are generally calm, keep in mind that if you do capsize, you will need to know how to roll or re-enter your boat or be faced with a long swim to shore. | |

| Traffic | Deep and wide water usually spawns powered vessels, from little pleasure skiffs to massive oil tankers. Keep your distance from motorised boats, learn the basic rules of navigation, and review notices to mariners on commercial waterways. Boat traffic may also be a factor on shallower upland rivers: popular fly fishing streams like the branches of the Delaware can be crowded with drift boats during trout season, and you can be bowled over by poorly-controlled commercial rafts in the rapids of the Lehigh. | |

| Seclusion | One does not need to go to Alaska to find a wilderness river. Some rivers described on this website, such as the Clarion and West Branch Susquehanna, have long stretches unparallelled by roads with banks devoid of human activity. Many more sections besides have poor or no cell service. These conditions make it much more difficult to call for or travel to help. When planning a trip on a remote section of river, consider learning wilderness survival skills and bringing additional equipment such as a satellite phone or locator beacon, and make sure to file a float plan. |

Things to consider

Before heading out to the river, here are some questions to ask yourself to assess whether you are prepared for your trip. You may not have answers to all these questions, and some answers will come only with experience, but these prompts are designed to get you thinking about all aspects of river safety.

External (pertaining to the river and its environment)

- River conditions. What are the river levels and flows? How do they compare to recommended levels, and how are they forecasted to change during my trip? What is the average current speed? What is the water temperature? If paddling a tidal river, when are high and low tides? Are there any visible hazards (floating debris, water up in the trees, algal bloom)?

- River characteristics. What is the gradient? Are there rapids, and if so, how difficult are they at present flows? Is the channel broad and straight, or narrow and meandering? Does the channel frequently braid around islands? Are there dams, shallow pipe crossings, low-water bridges, fences, or other river-wide obstructions?

- Other environmental considerations. What is the weather forecast? When is sunset? How closely or widely spaced are access points? What type of terrain does the river flow through (farmland, forest, urban)? Is there cell coverage on the river? What services are available ashore? Do powered boats use the river? Is there a designated navigation channel?

Internal (pertaining to the paddler and his/her interaction with the river)

- Knowledge and experience. Have I paddled this section of river before? Have I paddled it at similar water levels? If this is my first time on a particular river, have I paddled other similar-profile rivers? How adequate are my answers to the “external” questions above?

- Skill and fitness. Can I handle my boat comfortably in the anticipated river conditions? Am I reasonably proficient in the techniques needed to run the rapids I will encounter? Considering distance, current speed, and wind, do I have the endurance to complete this trip?

- Equipment. Am I wearing a PFD? Am I properly dressed for both the weather and the water temperature? Do I have protective and rescue equipment appropriate for the level of rapids I will be running? Have I packed a first aid kit? Do I know how to use all my gear? Do I have redundancy in critical equipment (spares or material and knowledge for repairs)?

- Other personal considerations. Am I feeling up for river-running? Do I have any misgivings about this trip? Might anyone in my party need special assistance (novice paddler, non-swimmer, medical condition)?

As you gain experience, you will begin to develop your own checklists tailored to the types of rivers you run, the gear you carry, and your preferred routines. The author chooses to note certain answers to the above questions on a self-crafted briefing form before each river trip. This is probably overkill for most, but for those who may find it useful, a blank template is provided. Pre-trip briefing items are highlighted in yellow; the remainder is filled out afterwards (completed example).

File a float plan

In aviation, a flight plan ensures that if the pilot goes missing, search and rescue personnel will initiate efforts in a timely manner and will know where to look. A float plan offers boaters the same advantage. If you become stranded, injured, or incapacitated on the river, having a float plan on file means that rescue authorities will be alerted to your potential plight even if you are unable to call for help. This is an especially important safeguard if you are paddling in a remote area or paddling solo.

In its simplest form, filing a float plan means telling a trusted friend or family member where you are paddling and when you will return. At its most thorough, a float plan is a document with detailed information about the paddler(s), boat(s) and equipment, put-in and take-out locations and times, and emergency contacts. A formal float plan also describes a protocol to follow if the paddler fails to check in or report the trip complete.

For those interested in the more thorough approach, the author recommends using the U.S. Coast Guard’s float plan template. (Note that this document is still filed with a friend or family member, not the Coast Guard.) Going through and filling out this form will help you cover all the bases in terms of information that could prove useful in a search and rescue operation. For example, finding the phone number of the appropriate rescue authority (usually a local fire department or park service) beforehand ensures that the float plan holder will not waste time looking up contact information in a possible emergency. The template also has a space for listing the parking locations of shuttle vehicles so authorities can check whether the paddlers have made it back to their cars. Finally, Page 3 lays out an unambiguous sequence of actions for the holder to take if the paddler becomes overdue or missing.

The author files a USCG float plan for every river trip, with instructions to contact her if she is one hour overdue (two hours if there is no cell reception at the take-out) and then execute Page 3 if she does not respond. This system has worked very smoothly, except for one time when she had the Upper Delaware NPS looking for her because the text message closing her float plan upon arrival in Callicoon had indicated sent but was never received. Oops! At least the float plan implementation went as intended.

A note on paddling solo

Many paddling websites, guidebooks, and organisations issue blanket statements about never paddling alone. Not so this one. The author acknowledges many reasons to paddle solo, from necessity (all would-be companions occupied on that rare beautiful summer day when the rivers are up and running) to simplicity (not having to manage the range of abilities and dispositions in a group) to preference (what is the river if not a reprieve from constant human interaction?). In fact, the author undertakes the vast majority of her river trips solo, and she firmly believes that with the appropriate precautions and preparation, solo paddling can be a safe and sublime experience.

That having been said, it must be recognised that by its very nature, solo paddling does carry an extra layer of risk. If you get stuck in a hole or pinned against a rock, nobody will be around to throw you a rope. If you capsize in deep water, you will not be able to call upon a friend to assist you in re-entering your boat or retrieving your gear. When you paddle solo, you become completely dependent on your own judgement, skill, and endurance, so you’d best ensure those are up to snuff. At the bare minimum, in addition to all safety measures you would normally take on any river trip, you should meet the following requirements before endeavouring a solo paddle:

- You must have sufficient experience with your vessel, such that you can control it expertly in conditions rougher than what you expect to encounter on your trip.

- Carry a repair kit and know how to make field repairs to your boat should it sustain significant damage.

- Gather as much knowledge as possible about the river you will be paddling, whether through prior non-solo runs or through guide materials, satellite maps, shore scouting, and conversations with other paddlers. Learn the locations of rapids, obstructions, trouble spots, access points, and navigational landmarks.

- Scout any rapid not of the simple read-and-run variety; never attempt such rapids blindly. If you believe that a rapid will challenge you to the limit of your ability, portage.

- If paddling solo on a remote river, you must have the means to signal for help or the skills and supplies necessary to survive for several days in the surrounding terrain.

- Always file a float plan. A formal, written plan with clear instructions on when and how to initiate search and rescue is strongly recommended.

Aside from additional safety considerations, solo paddling presents a host of logistical challenges surrounding the bothersome need for transportation upstream. The author’s tips for tackling this issue can be found under Resources.

See also: About | How to use | Resources